Sam was born in Hong Kong on October 2, 2006. He lived for the first six months of his life in Kunming, China (with us) and was a very active and healthy little boy. When he was just six months old, we brought him back to America to live for about nine months.

He was just about to turn 11 months old when he got his first virus. He woke up with a fever of 102.5F. He was a little out of it, but sitting on Bill's lap, when he had a febrile seizure. We called 911, went to the hospital and were sent home with the instructions that febrile seizures only happen once. Two hours after arriving home, he had another one and even vomited. His temperature was at 102.9 and climbing when he vomited again and had another febrile seizure.

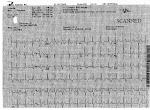

We called 911 and the EMT on the scene (Danny Nayman of Six Forks Fire Station in Raleigh, NC) couldn't get a pulse ox on Sam. He took an ECG on the ride over to the hospital and saw that Sam was in VTAC (his heart was beating over 300 beats per minute).

Rex Hospital thought the ECG was an artifact, as he was in a semi-regular rhythm when we arrived. No one had ever seen a child who was almost 11 months-old have VTAC before. The pediatrician on-call phoned every hospital in the area and there were no beds. Finally, UNC accepted us.

The doctor there recognized that Brugada Syndrome often masquerades as febrile seizures. He tested Sam with a simple 12-lead ECG (among other tests) and Sam was released from the hospital on Tuesday, with a cardiology appointment on Friday.

Two days later, I had a terrible headache. It was so bad that I couldn't stand or even sit up. We called my sister-in-law, Kendall, and she came over to take care of Sam that evening so I could go to the hospital. That night, I had a spinal tap and learned I had viral meningitis. It was especially difficult for us because I was still nursing Sam and wasn't able to do so, plus, Sam's cardiology appointment was the next day and I couldn't go. I stayed in the hospital for a few days, before they sent me home with instructions to rest and take medication. I was extremely sick.

Bill went to the cardiology appointment by himself. It was there he learned from Dr. Buck, Sam's cardiologist, that Sam had Brugada Syndrome. Dr. Buck recommended getting a second opinion, but that he thought Sam should have an ICD (internal defibrillator) implanted as soon as possible. Bill would later tell me that me being on drugs really helped him break the news to me (in the hospital). We spoke with a few other cardiologists, family members, and friends and decided to go ahead with the procedure.

Sam's surgery was scheduled for the following Tuesday. I couldn't make it to any of his preliminary appointments and barely made it to the actual day. Bill and his mother took care of the pair of us during the in-between time. Sam was put on a heart monitor at night, which would fall off constantly and cause Bill's own heart to stop. I had to stay downstairs in the house, because I could barely walk, so I wasn't a part of those horrible nights.

Sam's surgery went as expected. The surgeon said they had to test Sam's heart with the defibrillator to see if it was working properly. They sent his heart into VTAC seven times, but it kept coming out of it on its own, without the defibrillator's help. Finally, the 8th time, the defibrillator showed itself useful and shocked his little heart for the first time. The surgeon told us Sam's body was the smallest one he'd ever worked on.

They moved Sam to his room a little later, but something terrible happened. He was getting shocked over and over again for no reason. He was screaming in my arms as I held him - shock after shock riveting through his little heart. I'll save the conversation Bill had with the nurse for a face-to-face description, but it was the very hard for everyone. It was the longest I had stood up for a week and it was excruciating. Fortunately, Sam was so drugged-up that he likely won't remember it.

He received 22 shocks in 24 minutes. Dr. Buck came in as soon as he could and turned the unit off. We monitored Sam for another week in the hospital, with the unit's therapies (shocking portion) turned off. When we were finally satisfied that he was going to be okay, we turned it back on and went home.

During this time, our lives turned upside down. We thought we would be returning to China in January, 2008, but were quickly delayed until March, 2008. As time progressed, we learned that Sam's heart goes into VTAC every time he has a fever over 101.8F. He was hospitalized three or four more times in Raleigh (we called 911 each time) and went to the doctor countless times. He is so intimate with a stethoscope, he immediately picks up the end and holds it to his chest (and HAS done this since he was 12 months-old).

We delayed our return to China again, when he was hospitalized the fourth time. Dr. Buck suggested we wait another year and monitor Sam a bit before deciding what to do. Bill took a job with Samaritan's Purse and resigned from his position with Global Enterprise Services. It was a very difficult situation.

We are now in Boone, NC, where Bill worked for Samaritan's Purse. Sam was hospitalized twice after we arrived - one time he was sent via ambulance to Charlotte because his ICD shocked him five times. He had adenovirus and couldn't shake his fever.

God is at work in our lives and we have seen His hand on every aspect of every situation. We give all the glory to God for allowing Sam to be with us. We understand the leading cause of SIDS is Brugada Syndrome and that most children don't make it out of infancy. Brugada Syndrome is very rare and was only discovered in 1992.

I will update our blog as often as possible to allow you to follow our story. If you have any questions, please write me at teesa at mail dot com . I don't check that email address often, but will be happy to respond when I can.

Here is a copy of a letter Dr. Buck wrote to regarding our situation. It is based more on the facts of the situation and a little more technical.

Samuel was hospitalized at the North Carolina Children’s Hospital August 23-August 27 following seizures associated with fever. During transport to the hospital, EMS personnel acquired two ECG rhythm strips demonstrating rapid wide complex tachycardia. Subsequent ECG’s during that hospitalization and at Samuel’s outpatient follow-up visit demonstrated sinus rhythm with persistent but variable right bundle branch block pattern and ST elevation in the right precordial leads consistent with Brugada Syndrome.

Brugada syndrome was first characterized in 1991, but probably described anecdotally in parts for several decades...Brugada syndrome is typically recognized later in life (some series describe average age at diagnosis of 40 years), however it clearly affects young children as evidenced by Brugada’a first patient being two years old when first evaluated, and it has been recognized as one of the arrhythmia causes of SIDS. My understanding is that the youngest child diagnosed was 2 days old.

The risk of Brugada syndrome is the development of unstable life-threatening ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation. Interestingly, fever has been shown in adults and children to unmask or reveal Brugada syndrome, almost certainly because the affected ion channel in the heart works less well at above normal temperatures resulting in cardiac electrical instability.

At present, there are no uniform recommendations for anti-arrhythmia drug therapy for Brugada syndrome. There is emerging evidence that quinidine may be effective in reducing VT/VF episode frequency, which is a bit ironic since a major manufacturer of quinidine very recently announced its anticipation that it will be terminating its quinidine production. Risk stratification for Brugada syndrome continues to evolve. There does appear to be considerable hetereogeneity, even within families. For example I follow two adolescents (clearly affected based on their ECG’s and genetic testing) whose sister died suddenly as a teenager, my patients both have had defibrillators implanted for several years, yet neither has had device discharge or other evidence of VT or VF.

Of affected individuals, it is probable that roughly half represent new genetic cardiac ion channel mutations within that individual and the remainder are the result of autosomal dominant familial transmission (analogous to Long QT Syndrome). The genetic / cardiac ion channel causes of Brugada Syndrome are however not nearly as worked out as LQTS; only 1/3 – ½ of clinically diagnosed Brugada syndrome have abnormalities of the currently recognized genetic loci, the most common being the SCN5A cardiac sodium channel (interestingly the same gene and channel that when mutated in another way causes LQTS type3). A sample of Samuel’s blood has been sent to Dr. Charles Antzelevitch in Utica, NY for genetic testing (at no cost to the Klear’s); Dr. Antzelevitch is one of the country’s premier Brugada researchers. If Samuel’s genetic testing is positive, I’ve recommended both parents have genetic testing as well. We are in the process of having ECG’s of family members reviewed.

Based on Samuel’s documented rapid ventricular tachycardia, he was deemed at high risk of life-threatening arrhythmia. Placement of an ICD was recommended which was performed September 5, 2007. Intra-operative ventricular sensing, pacing, and defibrillation functions were appropriate; however several hours later just as Samuel was being transferred from the recovery room to the Pediatric Cardiology Intermediate Care unit for observation, he had a series of inappropriate device discharges delivering a number of 10 Joule shocks when in fact Samuel’s rhythm was sinus (with bundle branch block and prominent T waves). The cause of the inappropriate discharges appears to be the device mis-interpreting T waves as QRS complexes (in addition to the QRS’s) , thus resulting in double counting and thus the device achieving heart rate criteria for therapy delivery. Having spent many hours with Medtronic personnel in person and by phone following this storm of inappropriate shocks, it is likely a combination of multiple clinical features (some of which are particular to Brugada syndrome) and device signal processing algorithms resulted in the T wave over-sensing. We suspended the therapy delivery of the device for several days yet utilized the monitoring capacity of the device to monitor for any ongoing T wave over-sensing after the first post-operative overnight (there was none) and we subsequently re-activated the therapy delivery capacity, also with several days of hospital observation during which no over-sensing occurred. Lastly, when I saw Samuel on Friday morning September 14th as an outpatient, there had been no more over-sensed events.

12-Lead ECG showing some Brugada tendancies

Sam's first recorded VTAC, in the ambulance

Is there anyone among you who, if your child asks for bread, will give a stone? Or if the child asks for a fish, will give a snake? If you then, who are evil, know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will your Father in heaven give good things to those who ask him! Matthew 7:9-12 (NRSV)